I have always been a nerdy lover of books. Gigi, my super cute grandma, used to take me to the library every summer so that I could gather up a collection of books and read until I was rewarded with a fine, shiny medal, which I proudly wore.

At 22 years old, I still like to go to the library (or my friendly Amazon.com) to gather up a collection of books to read. The reward I claim is even better than a shiny medal. I gain insight into my world, myself, and everything in between.

And sometimes the reward, i.e. the insight, is a little bittersweet. In my reading today, I learned—or rather I learned to recognize—something slightly disturbing about myself: I often act from a sense of entitlement.

Why did it take me 22 years to figure this out? Because I grew up totally believing in equal opportunity and equal rights and all that American jazz. So for 22 years I’ve been making up excuses about why I “deserve” preferential treatment.

This is something the author of my Uprooting Racism book, Paul Kivel, taught me about myself. He lists a number of excuses in the book that I admit I have absolutely felt before:

At 22 years old, I still like to go to the library (or my friendly Amazon.com) to gather up a collection of books to read. The reward I claim is even better than a shiny medal. I gain insight into my world, myself, and everything in between.

And sometimes the reward, i.e. the insight, is a little bittersweet. In my reading today, I learned—or rather I learned to recognize—something slightly disturbing about myself: I often act from a sense of entitlement.

Why did it take me 22 years to figure this out? Because I grew up totally believing in equal opportunity and equal rights and all that American jazz. So for 22 years I’ve been making up excuses about why I “deserve” preferential treatment.

This is something the author of my Uprooting Racism book, Paul Kivel, taught me about myself. He lists a number of excuses in the book that I admit I have absolutely felt before:

1. I am better educated

2. I have more experience

3. I am more rational

4. My time is more valuable

5. I worked hard to get where I am

6. They probably don’t need as much to live on

7. I don’t actually have direct contact with them so I am not responsible

8. I need to get there on time

9. I’m doing more important things (this is my personal addition to his list)

These kinds of excuses are just the foundation of persistent inequality in our society. Most of us would never stand in a long line, see a person of color and think: “Because I’m white, I should be able to cut him/her.” We live in the twenty-first century.

But recognizing that we think in these more subtle terms of entitlement, as listed above, is almost worse because they’re so hard to be conscious of if they’re not brought to our attention. And furthermore, it’s kind of embarrassing to admit that we may think this way sometimes.

This sense of entitlement is a very surreptitious way of manifesting our latent beliefs that people really are unequal. I don’t mean in the sense of socioeconomics or politics (we all know that’s the case). I mean this sense of entitlement reveals a hidden belief that people are unequal at the human being level.

Let me paint a slightly humiliating picture. The time when my feeling of entitlement is most noticeable is when I’m in the car and I am in a serious hurry to get somewhere. If I’m in a hurry to get somewhere, it is obviously somewhere important that I need to be. So typically, I get extremely frustrated (and frustrated is a euphemism) when other people get in my way, go below or at the speed limit, or just look at me.

My thoughts, which are peppered with expletives I won’t write out, follow these lines: “Why the hell are you in the fast lane when you’re going the speed limit?” “I HAVE SOMEWHERE TO BE!” “DEAR GOD, YOU SHOULDN’T BE DRIVING!” “I don’t have all day, and you clearly don’t have anywhere to be.” “WHY ARE YOU ON THE ROAD?!”

And my actions follow these lines: I weave in and out of cars. I tail cars that won’t yield to me. I throw up my hands in the air to signal my frustration so they can see. I speed past people when they finally move over and then I glare hard core.

All of these thoughts and actions are just the manifestation of me thinking I deserve the road more than anyone else because I “have somewhere to be,” automatically assuming that no one else does because they’re not as important as I am.

That’s hard to admit, and I’m definitely not thinking that explicitly when I act or think that way. But we really do rarely look at the root of the reasons we say or do things. Beneath the superficial reasons, there is usually a much bigger reason for the way we act than we’re willing to admit.

But if we can come forward, see where we err—even when it is incredibly embarrassing in retrospect (like my road rage)—we can really begin to address the ways in which the culture of power is ingrained in us. That culture of power is characterized by a sense of entitlement at the expense of others.

Am I going to be an angel every time I drive in my car, even and especially when I’m late and in a hurry to get somewhere that is important to me, now that I recognize what my actions mean? Probably not likely. But I will certainly be more conscious and aware of what my actions imply about my beliefs.

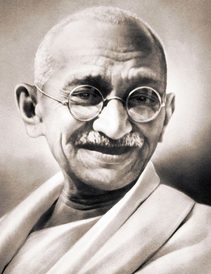

It was the great Mahatma Gandhi that wisely said:

But recognizing that we think in these more subtle terms of entitlement, as listed above, is almost worse because they’re so hard to be conscious of if they’re not brought to our attention. And furthermore, it’s kind of embarrassing to admit that we may think this way sometimes.

This sense of entitlement is a very surreptitious way of manifesting our latent beliefs that people really are unequal. I don’t mean in the sense of socioeconomics or politics (we all know that’s the case). I mean this sense of entitlement reveals a hidden belief that people are unequal at the human being level.

Let me paint a slightly humiliating picture. The time when my feeling of entitlement is most noticeable is when I’m in the car and I am in a serious hurry to get somewhere. If I’m in a hurry to get somewhere, it is obviously somewhere important that I need to be. So typically, I get extremely frustrated (and frustrated is a euphemism) when other people get in my way, go below or at the speed limit, or just look at me.

My thoughts, which are peppered with expletives I won’t write out, follow these lines: “Why the hell are you in the fast lane when you’re going the speed limit?” “I HAVE SOMEWHERE TO BE!” “DEAR GOD, YOU SHOULDN’T BE DRIVING!” “I don’t have all day, and you clearly don’t have anywhere to be.” “WHY ARE YOU ON THE ROAD?!”

And my actions follow these lines: I weave in and out of cars. I tail cars that won’t yield to me. I throw up my hands in the air to signal my frustration so they can see. I speed past people when they finally move over and then I glare hard core.

All of these thoughts and actions are just the manifestation of me thinking I deserve the road more than anyone else because I “have somewhere to be,” automatically assuming that no one else does because they’re not as important as I am.

That’s hard to admit, and I’m definitely not thinking that explicitly when I act or think that way. But we really do rarely look at the root of the reasons we say or do things. Beneath the superficial reasons, there is usually a much bigger reason for the way we act than we’re willing to admit.

But if we can come forward, see where we err—even when it is incredibly embarrassing in retrospect (like my road rage)—we can really begin to address the ways in which the culture of power is ingrained in us. That culture of power is characterized by a sense of entitlement at the expense of others.

Am I going to be an angel every time I drive in my car, even and especially when I’m late and in a hurry to get somewhere that is important to me, now that I recognize what my actions mean? Probably not likely. But I will certainly be more conscious and aware of what my actions imply about my beliefs.

It was the great Mahatma Gandhi that wisely said:

Fortunately, all of these things are in our control. With practice and dedication we can be and become exactly who we want to be.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed